–

–

How was the world made?

Is there life after death?

Why does life fold in this and not in any other way?

How should we live?

–

These are the questions that each of us poses to himself at least once in a lifetime. If we want to find answers by rational thinking, while employing the scientific method, we are already dealing with philosophy and thinking about the basic philosophical themes. The paper will firstly discuss the issue of defining philosophy as a science before proceeding to attempts to explain the reasons why Freemasonry in truth represents a practical philosophical system. The latter issue will bring into question the foundations on which the philosophy of Freemasonry came into existence as well as where it started before getting to the point it has reached nowadays. Finally attempts are made to underline elementary attitudes of a Freemasonry approach to philosophical issues.

–

1. A Little Something about Philosophy

To provide an answer to the question „What is philosophy?“ is at the same time both easy and difficult. For our needs here it is sufficient to first of all quote one of the textbooks used by the students of Oxford stating that „philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with reality: existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language.” In the Vujaklija lexicon of foreign words and terms philosophy is defined as “a scientific work on building a general view of the world and this very worldview itself.” Let’s conclude the definition of philosophy here with a well-known fact that the very word philosophy comes from the ancient Greek word φιλοσοφία which literally means “love of wisdom.”

Man has been dealing with philosophical issues for more than 2500 years while trying to decipher the basic phenomena of human existence. In its studies of the problems of enlightenment and revelation, philosophy was intertwined, in the Old and Middle Ages, with religion and natural sciences. Contemporary philosophy has, from the 17th century onward and due to the development of academic approach, succeeded in diverging from the ancient and medieval philosophy and, to an extent, in narrowing down the issues it is concerned with. The basic philosophical methods are analysis, synthesis, interpretation and speculation.

In order to round up the definition of philosophy, we shall, finally, enlist the basic branches it is the study of. The aim of this enlisting of scientific fields is to make us recognize the problems that we, as Masons, deal with at our workshops. The basic branches of philosophy are:

Ontology or “metaphysics” is the study of the most general features of the overall reality or the being of all existing. “Being” is one of the basic concepts that pure philosophy deals with and is interpreted as the foundation of existence which is unconditioned, i.e. an absolute or substance.

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy dealing with the basic principles of cognition, that is, it studies our cognition apparatus and its functions. The theory of cognition studies emergence, possibilities, and limits of human cognition.

Logic is a philosophical discipline that studies the basics of thought or valid reasoning such as deduction and induction.

Ethic is about studying the concepts of good and right. Its subject is moral. Ethic tries to decode the motives of human action and moral judgment.

Aesthetic studies the beautiful and the valuable. Its object of study is artistic creation and the basic questions it seeks to answer to are: what is the essence of artistic creation and what is the essence of the experience of artwork?

Other philosophical branches include axiology, anthropology and some other ones whose more detailed explanation here would lead us far from our set topic.

–

2. Influences and Foundation That Freemasonry Philosophy Was Built Upon

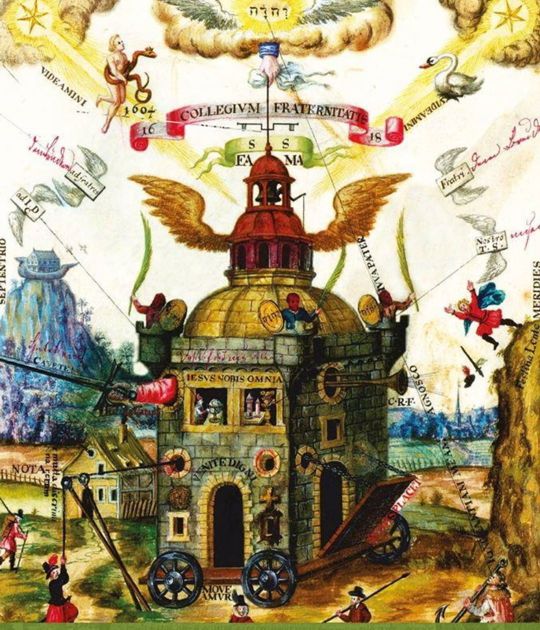

Beyond any doubt is a continuous line of cherishing the symbols and rituals of the veiled knowledge that is gradually revealed only to the chosen and the illuminated. This line started with the rites of old Egyptian priests as well as legends about Egyptian deities through ancient Greek schools of mysteries, early Christian Essenic communities at the Near East, the Knights Templar and Rosicrucian societies, and further on till the present day. Yet here we are not going to examine this romanticized approach to the history of Freemasonry and Masonic symbolism. Rather we are going to try to say something about the philosophy of Freemasonry at the moment of the ritual formation and the basic symbolism that we recognize in practice today. The moment we refer to is actually the one of the emergence of speculative Freemasonry dating the first half of the 17th century on the territory of the present day Western Europe. This is the very end of the period otherwise known as the Humanism and Renaissance. In the domain of philosophy this is the period of the flourishing of the new philosophical thought. After centuries of darkness and unquestioned rule of the church which had, among other things, through the Inquisition, extirpated from its very roots any possibility of a different opinion, there came an explosion in the development, first of all, of arts and then of science. It is likewise the time when the basic symbolism, legends and allegories were formed, namely, those through which we today recognize the philosophy of Freemasonry.

Till the Renaissance came to the scene, a very few philosophers involved in the study of the basic philosophical themes came to, even for a moment, questioning the leading church dogmas. All their efforts aimed at finding the ways of somehow inputting the teachings of the ancient Greek philosophers into the dominant Christian doctrine. The Renaissance changed all this; it led to setting up a new attitude to God. Philosophy and science gradually departed from theology while the attitude to reality came to be formed on the basis of perception, measurement and experiment. It is man who became the centre of interest. A personal attitude of man to God became more important than his attitude towards ecclesiastical institutions. The outcome of this individualization of the attitude to religion, in the period of the Late Renaissance, led to the emergence of the Reformation as well as new denominations within the Christian religion.

The best known philosophers, at the beginning of the Renaissance period, turned to man. Ficino says, “Know thyself, O divine lineage in mortal guise!” Pico Della Mirandola wrote an oration entitled Oration on the Dignity of Man. During the dark Middle Ages the church dogma insisted on man’s sinful nature while, starting from the classical humanism, the Renaissance philosophers began to regard man as something infinitely grand and valuable. The early Renaissance thought can be described as a fusion of the Judeo-Christian tradition and knowledge most concisely written down in two seminal books, Hermatica and Kaballah. Hermetica was completed, in Constantinople in 1050, by the respected Byzantine philosopher and historian Psellus. The content of the book is basically Hellenized philosophy of ancient Egypt. Kaballah as a mystical interpretation of Judaism was given its final shape by the Spanish Sephardi Jew Moses de León in the late 13th century. The basic characteristics of the Renaissance philosophical thought built upon these models are: Neoplatonism, interconnectedness of the divine and the earthly (assuming that these two worlds complement and balance each other) and the belief that the revelation and cognition of the divine are in effect a personal experience that everyone achieves on his own, independently of the experience of others. Let’s say a few words about each of these basic characteristics of the Renaissance philosophical thought:

– Neoplatonist understanding of the world is founded on the fact that God is infinite. Unlike the church dogma which separates the creator from his work, the Neoplatonists hold that in his creation God built himself into his work and continues to exist through it. His creations are the whole universe and all life in it. The line between matter and spirit is blurred. In every man there is a divine sparkle shining.

– From the idea of interconnectedness between macrocosm (Universe) and microcosm (man) there also follows a view that the divine, that is, spiritual part of the reality is intertwined, through intricate relations, with the earthly, that is, material part. All that happens in one sphere is at the same time reflected and has an impact upon the other sphere. For instance, the stars and planets affect human behavior through different invisible forces. The key for understanding the spiritual world are symbols.

–

– An individual can get to know God only through personal experience and even this only after a devoted work upon himself. Revelation is a personal experience and no acceptance of someone else’s experience of revelation is helpful in this case since this would be a dogma. Everyone should invest his own effort and in his search for truth he can finally get to know the divine in himself. “Perennialism” or “eternal philosophy” speaks about this very phenomenon and holds that this mechanism is recognizable in all the known religions. The universal truths that will one day reveal themselves to believers are at the very core of every major religion and are all the time revealed anew by the very founders of these religions. Though the religions sometimes differ considerably or even oppose each other, still in all of them can be found a common teaching about the ultimate meaning of life. The advocates of perennialism hold that the act of unity of human soul and a higher authority is possible only through “self-development” and “purification.”

Following the above-given guiding principles did the Masonic rites come into being, legends and symbols in the form that we recognize at present. By a close analysis of each of the basic Masonic symbols it becomes easy to identify the sources in the Judeo-Christian and hermetic symbolism of the Late Renaissance. The recognition of the roots that brought to Freemasonry two pillars, the chess board, the blazing star, the spiral staircase, the legend of Hiram Abiff and other symbols and legends is beyond the scope of this text; yet by analyzing the sources mentioned here it is possible to easy detect their origin. However, it is quite a long path leading from the original symbolism and early rites from the early 17th century to the practical philosophical system we possess today.

After the above-mentioned explosion in the field of art preceding the one in the field of science that were both brought about by the Renaissance, there came one after another great thinkers and philosophers and, thanks to them, the major works that marked the years thereafter. Along with the progress of science there came narrow specialization in exploration as well as constant fragmentation of knowledge which would very soon cause the general image to disappear from the scientists’ focus. This is especially evident in the fundamental scientific bearings related to physics, chemistry, medicine and other natural sciences. Yet fragmentation of sciences was by no means something that the social sciences were immune to. Contrary to fragmentation, some thinkers tried to point to the fact that it is very important to work upon integration of knowledge which represents a central idea of the Masonic approach as well. A decisive moment after which the Masonic approach to the philosophical issues became theoretically founded comprises the works of several thinkers including, most surely, the most important of them all, Carl Gustav Jung. For this reason we are going to devote slightly more attention to him.

–

3. A Little Something about Carl Gustav Jung

The end of the 20th century and the present age are under the sign of the philosophical approach known as Existentialism. Yet, for an understanding of the Masonic philosophical system of great importance is the work of the Swiss thinker Carl Gustav Jung who lived and worked just before the emergence of the best known Existentialists. Only after the publication of the works of this Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, scientist and thinker, did the Masonic worldview get its scientific solemnity.

With his theory of archetypes and collective unconscious Jung caused a genuine revolution in the field of understanding human nature. By analyzing dreams, myths, rituals and the medical practice he was involved in, Jung introduced into science the concept of the unconscious beyond the personal as a new inner layer hidden deep under the individual unconscious. Since the individual unconscious had already been thoroughly investigated in the works of Sigmund Freud, the collective unconscious emerged as an entirely new concept. In the collective unconscious there lies hidden a spiritual experience accumulated over the centuries, from previous generations, consisting of a variety of archetypes. In his debates he explained the archetypes of mother, divine birth, rebirth, spirit and other ones appearing in fairy tales, religions, esoteric teachings and myths.

After Jung nothing was the same as before. An especially dramatic change was undergone by the humanist sciences and all kinds of art (literature, painting, all of them up to music and film).

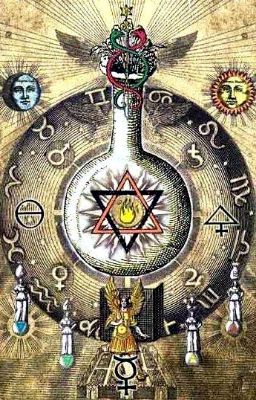

For us, Masons, of special importance are Jung’s works written in his later years when, in searching for pre-archetypes of the collective unconscious, he delved into the world of alchemy and started to explore the works of Agrippa and Paracelsus. If we cast a cursory glance at alchemy as a process of obtaining gold from lead by the chemical reactions induced in a glass crucible, we are prone to characterize it lightly as a meaningless and vain magic rite. However, Jung discovered the true nature of medieval alchemic processes and explained it in a book published in 1944 entitled Psychology and Alchemy. For a Jung’s alchemist the matter he studies and tries to change is a great mystery and it is due to this fact that, in a collision with the unknown, the alchemist witnesses an apparition of the unconscious before him: from the depths of the spiritual heritage there arise images and happenings by which a cognitive process is actually established. Thanks to the cognition initiated in this way, he begins to understand what he is doing. A psychic experience and a cognitive process in the alchemist’s mind, caused by his alchemist experiment, irresistibly resemble chemical reactions of one chemical compound transforming into another. An analogue to “pure gold” in the material aspect of the experiment becomes, in the spiritual domain, “a stone of wisdom.” During the alchemist procedure the alchemist himself undergoes transformation; thus he himself becomes an object of spiritual transmutation. For Jung matter is not just an impersonal set of atoms. The very eternity as an immanent property of matter makes it the carrier and keeper of the divine touch.

One of the most important principles that Jung the alchemist stressed is the unity of opposites. Dualism in everything surrounding us and the birth of a new quality in the reaction of two opposite elements are the very essence of the experiment. In the process of metamorphosis of the “lead” earthly impurity into “gold” of spiritual perfection, the crucible is the alchemist himself. Dealings with modern alchemy, for Jung, is but a long-lasting and painful process of gaining self-knowledge that he, in his works, names the process of individuation. In his book Introduction to the Religious and Psychological Problems of Alchemy, Jung goes even further in comparing a “stone of wisdom” to Jesus Christ – but this topic requires much more than available space here.

In conclusion to this section of the text devoted to Jung, we should say that he did not require his followers to deal with alchemy; rather, he wanted to inspire each of them to initiate his own inner wheel and indulge himself in the magic of his inner being metamorphosis. This process we can name any way we want. He called it individuation while the Freemasons call it a path to Light. All we do in our Masonic workshops incontestably resembles the alchemic procedure described and explained by Carl Gustav Jung.

–

–

–

4. Freemasonry as a Practical Philosophical System

The key Freemason allegory about a path from darkness to light is recognized in all religions while it originates from Old Egyptian initiations and ancient mysteries. They all have in common the theme of man who, by the very Creator’s act, used to have all and was perfect but yet fell down and was expelled from a higher sphere of existence; that is why he today roams all over earthly waste lands searching for what he had lost. Lost is his genuine and original nature as well. From the center of life is mankind expelled to the periphery and that is why it is doomed to wander as captured in the present, constrained by its imperfections and ignorance. Yet learning, discipline and fortitude can enable an individual to create an opportunity and go back to where he once belonged – to his “paradise lost.” The secrets of our genuine nature are temporary hidden while our capacities to discover them are lessened due to the difficulties brought about by our everyday life. By building a temple with us, who are its builders as well as building material, Freemasonry points to us a pathway for finding what we have once lost.

If we interpret the allegory about a path from darkness to light in this way, then we can state that Freemasonry is a practical philosophical system since it offers answers to the questions we have posed at the beginning of this paper. The question of all questions is, “What is the meaning and what is the purpose of our life?” Even to this is Freemasonry offering us a practical answer by showing to us where we come from and where we are to return one day. If God is a circle whose center is everywhere (as spoken to us by one of the basic Masonic symbols), then the divine center, the principle of life and infinity, is in our own selves.

Superficially, the Freemason teaching can leave an impression about its being a set of morals that could be found elsewhere as well. Formally, no big difference exists between the morals defined by God’s Ten Commandments and those in the Freemasonic Decalogue since in both the cases what is good is recommended while what is bad is prohibited. However, a difference exists and it stems from the simple fact that a Freemason thinks about the morals during the ritual work in the protected Lodge which is, in all that time, outside “time and space” while he raises his heart and opens up his mind. The Freemason understands that the secrets he reveals are not on the surface; neither are they hidden in verbal bravura but in the spiritual sphere.

Let’s round up the paragraph about Masonic philosophy with a few elementary principles that we, Freemasons, today hold as guides:

–

– Creator is one and his name and nature are irrelevant.

– Man is made up of spiritual and material parts.

– This earthly and temporary nature of the material part makes people imperfect and prone to mistakes. By working on ourselves we are trying to bring our spiritual part to balance with the material one.

– Our goal is to get to know the Creator and achieve harmony with the universe surrounding us.

–

5. Something like a Conclusion

Though for us, Freemasons, Freemasonry unequivocally represents a complete philosophical system, the question still remains whether it is the same for profane world which regards it with more doubts and much more critically. Judging by the themes that the initiated is dealing with, on his Masonic path, the contemporary Freemasonry surely satisfies all our inner needs. Yet, the question whether the Masonic philosophy is sufficiently scientifically-based is not easy to answer.

In our attempt to give some kind of answer, we shall make an analogy with another question which will take us back to Carl Gustav Jung. We shall take into consideration an interesting dilemma asking whether Carl Gustav Jung is a scientist or mystic. Did he, in his later years, betray a scientific method and turned to the occult? To apply the practical method to checking whether Jung’s claims about alchemic processes are correct requires us to invest at least the same amount of time and effort that he himself invested in his own research. Whether Jung experienced any revelation and penetrated into the secrets of the soul transmutations is something we cannot surely know today. The foreknowledge he had as well as energy and years he invested into research, no less than the conclusions he reached, unequivocally show that alchemy is not a stupidity. However, it is possible that he discovered only one side of alchemy of man’s inner being while we, if we persist along our pathway, may discover some other. Is there any sense at all in following his path if it is possible to get to the same results by some other much simpler means? Are the scientists at Cern, those who are trying to single out “god’s particle” from atom, on the same task of searching for a “stone of wisdom” but only by another pathway and by using some other tools? Will they, at the end of the path, also be experiencing the cognition of the divine sparkle in man?

The truth that we, Freemasons, should be guided by in our everyday life is, actually, not so complicated as it seems at first sight. The moral from the following quote gives us quite solid guidelines just as it sufficiently motivates us to persist on our pathway from darkness to light:

–

The purpose of man is nowhere else but in man himself.

Our final yet unattainable goal is perfection.

However, our attainable goal is constant improvement…

–